|

This blog was started at the behest of colleagues who requested for more info on Human Error. We explored various types of Human Errors, the telltale signs of error prone conditions and how to have a degree of control over Human Error in our organizations. There is absolutely no way of eliminating Human Errors. We can at best learn to recognize and build resilience to reduce the risk of single error leading to a disaster. It can get very low, but it will never reach zero!

Showing posts with label EASA. Show all posts

Showing posts with label EASA. Show all posts

Friday, May 19, 2017

PFRAT - The Mobile App to prevent Aircraft Accidents!

Labels:

Accident,

Accidents,

Aircraft,

Airline,

Airport,

App,

Aviation,

classification,

crash,

EASA,

Error,

Human,

investigation,

mobile App,

Safety,

Violation. mobile

Sunday, July 19, 2015

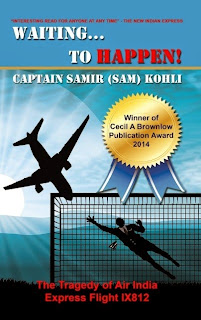

EASA Task Force Report on #GermanWings 9525 - A tale of missed opportunities and Accidents "Waiting...To Happen!"

The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) was tasked by the

European Commissioner to establish a Task Force to look into the accident of #GermanWings

flight 9525 including the findings of the French Civil Aviation Safety

Investigation Authority (BEA) preliminary investigation report.

Chaired by EASA Executive Director, the Task Force consisted

of 14 senior representatives from airlines, flight crew associations, medical

advisors and authorities. Additional contributions were provided by invited

experts and representative bodies. Three formal Task Force meetings took place

from May to July 2015.

As a result of its work, the Task Force delivered a set of 6 recommendations to the European Commission on 16 July 2015, as

follows:

- Recommendation 1: The Task Force recommends that the 2-persons-in-the-cockpit recommendation is maintained. Its benefits should be evaluated after one year. Operators should introduce appropriate supplemental measures including training for crew to ensure any associated risks are mitigated.

- Recommendation 2: The Task Force recommends that all airline pilots should undergo psychological evaluation as part of training or before entering service. The airline shall verify that a satisfactory evaluation has been carried out. The psychological part of the initial and recurrent aeromedical assessment and the related training for aero-medical examiners should be strengthened. EASA will prepare guidance material for this purpose.

- Recommendation 3: The Task Force recommends to mandate drugs and alcohol testing as part of a random programme of testing by the operator and at least in the following cases: initial Class 1 medical assessment or when employed by an airline, post-incident/accident, with due cause, and as part of follow-up after a positive test result.

- Recommendation 4: The Task Force recommends the establishment of robust oversight programme over the performance of aero-medical examiners including the practical application of their knowledge. In addition, national authorities should strengthen the psychological and communication aspects of aero-medical examiners training and practice. Networks of aero-medical examiners should be created to foster peer support.

- Recommendation 5: The Task Force recommends that national regulations ensure that an appropriate balance is found between patient confidentiality and the protection of public safety. The Task Force recommends the creation of a European aeromedical data repository as a first step to facilitate the sharing of aeromedical information and tackle the issue of pilot non-declaration. EASA will lead the project to deliver the necessary software tool.

- Recommendation 6: The Task Force recommends the implementation of pilot support and reporting systems, linked to the employer Safety Management System within the framework of a non-punitive work environment and without compromising Just Culture principles. Requirements should be adapted to different organisation sizes and maturity levels, and provide provisions that take into account the range of work arrangements and contract types.

Following the 11 September 2001 attacks, several measures

were introduced to mitigate the risk of unwanted persons entering the cockpit.

Secure cockpit door locking was rapidly mandated, and rules were subsequently

fine-tuned to address the risks in the areas of rapid aircraft

depressurisation, double pilot incapacitation, post-crash cockpit access, and

door system failure including manual lock use.

The focus for all the measures that were introduced was put

on the threat from outside of the cockpit. A potential threat from inside the

cockpit was not fully considered in either the initial phase or the period that

followed, when the regulations were fine-tuned.

As I have also pointed out in my earlier blog posts in this

blog, the risk mitigation measure introduced to mitigate the risk of unlawful

interference (Secured Cockpit Door) has actually facilitated the very event it

was meant to prevent! There have been many cases, even before #GermanWings

9525, where the secure cockpit door was locked from inside by a rouge pilot,

preventing the other pilot from entering, while he proceeded to unlawfully

interfere with the flight by hijacking or crashing it. The risk mitigation

measure had been introduced and implemented in a hurry, without a full

assessment of Residual Risks or Additional Risks created by its implementation.

This was a mandate that the EASA task force was charged

with. Here was an opportunity to carry out a professional risk assessment and

properly evaluate all the additional/residual risks and develop a system to

mitigate them as well. Here was an opportunity to reform the cockpit door

technology and to improve the procedures surrounding its use. Here was an

opportunity to, maybe, introduce new technology; develop new policies and/or

new procedures.

Unfortunately, the task force has missed the bus! They have

chosen to limit themselves to the “2-persons-in-the-cockpit recommendation”,

instead of being more creative and developing further on this base to introduce

more security measures in addition to merely two-persons-in-the-cockpit. The

technology today has advanced considerably since the days of 2001 and many

additional and secure measures are today possible beyond the mere four digit

numeric code to lock or open a door. These additional measures, like biometrics

etc., are not only readily available but are competitively priced and readily implementable.

I was reminded by my colleague, Carlo Cacciabue, of

Professor James Reason’s ground breaking research and work on Safety Management

Systems. He used to say, mistakes by humans, be they errors or violations, are

like mosquitoes. You can try to swap them individually, but they will keep

coming back. The only way to save ourselves from being bitten is to drain the

swamps where these mosquitoes breed. All human performance happens inside an

organizations policies and procedures. Erroneous or insufficient policies/procedures

are the swamps where these mosquitoes called errors and violations breed. Unless

we develop organizations measures to prevent breeding of these mosquitoes, we

will never be able to prevent another event like #GermanWings 9525!

It is very unfortunate that the EASA Task Force has failed

to deliver any meaningful recommendation. One did not need a task force to

arrive at the very basic and on-the-surface kind of recommendations that have

emerged here. We all knew this within days of the accident. What one expected

from a task force of this level was a more professional risk assessment and

recommendations in tune with the complexity of the problem. The task force

needed to go into the depth of this problem and emerge with recommendations

with far reaching impact on safety of civil aviation. It needed to develop

organizational policies and procedures for dealing with distressed employees

and those that need help, in addition to a complete relook and revamp of how we

secure our cockpits.

Once again, it has been forgotten that at the end of the

day, pilots are as human as rest of us and susceptible to as many human

problems and issues as the rest of us. Any human can be regulated only to a

certain extent. There is a limit to the amount of stress and regulation that

can be piled onto a specific job role. The Pilots are the goal keepers of the

Aviation industry…and a goal keeper can only save so much if rest of the team

does not support the aim of winning the match!

An opportunity has been missed, and yet another accident, similar

to #GermanWings remains waiting…“Waiting…To Happen!”.

Stay Safe,

The Erring Human.

Labels:

Accidents,

Aircraft,

Airline,

Airport,

Aviation,

classification,

crash,

EASA,

Error,

France,

Germanwings,

Germany,

Human,

investigation,

journalism,

Lufthansa,

Passenger Rights,

Safety,

Violation

Sunday, May 10, 2015

#Germanwings 9525: Preliminary report and way ahead

The investigation team, under the

lead of French BEA, has published a preliminary report on the accident to

#Germanwings flight 9525 and the full report can be access here: http://www.bea.aero/docspa/2015/d-px150324.en/pdf/d-px150324.en.pdf

While the report does not tell us

too much more than what has already been made public in the press, it does

clarify some important technical doubts that have been voiced in various social

media as well as my earlier posts.

On the issue of “Human

Breathing”, the report states as follows, Quote “A sound of

breathing is recorded both on the co-pilot track and on that of the Captain

throughout the accident flight. This breathing, though present on both tracks,

corresponds to one person’s breathing. It can be heard several times while the

Captain was talking (he was not making any breathing sound then) and is no

longer heard when the co-pilot was eating (which requires moving the microphone

away or removing the headset). The sound of this breathing was therefore

attributed to the co-pilot.” Unquote.

It is very interesting to note

that even the Captains microphone recorded only the Co-pilots breathing, while

not recording Captains breathing or even that of the flight attendant who was

present in the cockpit for a short period of time. As I had mentioned in an

earlier post on this blog, if any sound of breathing is recorded in a CVR tape,

it cannot be normal breathing. This statement is now corroborated by the fact

that even the Captains mic, that was very close to his face, recorded only the

Co-pilots breathing and not of the Captain. We have evidence here that the

Co-pilot was certainly not breathing normally, and not just when the Captain

was absent from the cockpit! The co-pilot was clearly in distress on that

fateful day and it is surprising that this very audible sign was missed by all

around him. There is certainly a need here to probe deeper into this aspect of

evidence and if the crew underwent any nature of pre-flight medical evaluation

on that day or, if this heavy and abnormal breathing was also noticed by any of

the ground crew (eg. Flight Despatchers) who interacted with the Pilots prior

to departure and while on ground in Barcelona. It will also be significant here

to understand if there was any change in the rate, volume or frequency of this

breathing sound, especially at the time when Captain left the cockpit.

Another very significant detail

in this report is the revelation of what transpired during the onward flight to

Barcelona. The Captain apparently left the cockpit at 07:20 hrs. The aircraft

then received instructions to descend from its cruise altitude of 37,000 ft to

initially 35,000 ft and later to 25,000 ft. and the co-pilot descended the

aircraft according to these instructions, stabilizing correctly at 25,000 ft.

So far nothing is unusual. What is surprising here is the manner in which this

descent was carried out by the Co-pilot. Instead of making a selection to

35,000 ft and later changing that to 25,000 ft, he appears to have been

“playing around” with the auto-pilot controls. As the graph below depicts, he

made multiple, seemingly random changes, varying from the minimum possible

selection of 100 ft to the maximum possible selection of 49,000 ft! This behaviour

is highly unusual and needs some evaluation. The press is going viral calling

it a practice of what was to follow or even an aborted attempt to intentionally

crash the aircraft. However, to my mind, this might represent something very

significantly different. To me, this represents the behaviour of someone

experiencing psychomotor problems…essentially, a lack of coordination between

mind, eyes and hands! He seems to be hunting for the correct selection and

unable to reach one. It could also represent a casual attitude or lack of

seriousness, even indecisiveness. All of these could, in turn, be related to

the reported psychological distress caused either because of mental depression

or maybe, a more serious and undiagnosed state of Schizophrenia.

While the aircraft was correctly descended according to ATC instructions and stabilized at the requested level, the manner of achieving this was irregular and reflective of state of mind of the pilot. A deeper psychiatric evaluation is certainly necessary here and I hope BEA is investing sufficiently into such nature of professional evaluation.

A similar behaviour is also noted

in the minutes leading to the crash. The report states,

“At 9 h 33 min 12 (point 5), the speed management changed from “managed”

mode to “selected” mode. A second later, the selected target speed became 308

kt while the aeroplane’s speed was 273 kt. The aeroplane’s speed started to

increase along with the aeroplane’s descent rate, which subsequently varied

between 1,700 ft/min and 5,000 ft/min, then was on average about 3,500 ft/min.

At 9 h 33 min 35, the selected speed decreased to 288 kt. Then, over

the following 13 seconds, the value of this target speed changed six times

until it reached 302 kt.”

Once again, we see evidence of

“playing around” with speed selections…either unable to make a selection or

undecided on what selection to make, or maybe just playing with the selector

knob like a fidgety child.

Another significant aspect

highlighted in the report occurred just after the Captain left the cockpit. The

event is documented as follows:

- At 9 h 30 min 24 (point 3), noises of the opening then, three seconds later, the closing of the cockpit door were recorded. The Captain was then out of the cockpit.

- At 9 h 30 min 53 (point 4), the selected altitude on the FCU changed in one second from 38,000 ft to 100 ft. One second later, the autopilot changed to “OPEN DES” mode and autothrust changed to “THR IDLE” mode. The aeroplane started to descend and both engines’ rpm decreased.

- At 9 h 31 min 37, noises of a pilot’s seat movements were recorded.

- At 9 h 33 min 12 (point 5), the speed management changed from “managed” mode to “selected” mode. A second later, the selected target speed became 308 kt while the aeroplane’s speed was 273 kt. The aeroplane’s speed started to increase along with the aeroplane’s descent rate, which subsequently varied between 1,700 ft/min and 5,000 ft/min, then was on average about 3,500 ft/min.”

The Co-pilot was seated and

settled in his seat. He had been flying for some time. So, why at this point

should there be any need to move/adjust his seat? Did he at this point move

from his seat to the Captains seat? Did he have a reason to leave his seat? It

will be significant to note if there were any changes in his breathing pattern

at this stage because then there is another item in the report that causes

concern. The report documents, “low

amplitude inputs on the co-pilot’s sidestick were recorded between 9 h 39 min

33 and 9 h 40 min 07” and then again, “An

input on the right sidestick was recorded for about 30 seconds on the FDR 1 min

33 s before the impact, not enough to disengage the autopilot.” Both these

texts refer to the same event, although they appear in different sections of

the report.

Was this a last minute attempt by

a man struggling to regain control of his own body to recover and save the

situation?

Yet another significant aspect of

this report relates to the cockpit door access alarm. “At 9 h 34 min 31 (point 7), the buzzer to request access to the cockpit

was recorded for one second.” Further,

- the cockpit call signal from the cabin, known as the cabin call, from the cabin interphone, was recorded on four occasions between 9 h 35 min 04 and 9 h 39 min 27 for about three seconds;

- noises similar to a person knocking on the cockpit door were recorded on six occasions between 9 h 35 min 32 (point 9) and 9 h 39 min 02;

- muffled voices were heard several times between 9 h 37 min 11 and 9 h 40 min 48, and at 9 h 37 min 13 a muffled voice asks for the door to be opened;

- noises similar to violent blows on the cockpit door were recorded on five occasions between 9 h 39 min 30 and 9 h 40 min 28;

- low amplitude inputs on the co-pilot’s sidestick were recorded between 9 h 39 min 33 and 9 h 40 min 07;

In the description of the door

locking system fitted in the accident aircraft, it states that, “…To request access to the cockpit from the

passenger compartment, the normal one-digit access code followed by ‘‘#’’ must

be entered on the keypad. A one-second acoustic signal from the buzzer sounds

in the cockpit to warn the crew that someone wishes to enter…The flight crew

then moves the three-position switch:

- If they pull and maintain the switch in the UNLOCK position, the door unlocks. The acoustic signal stops. The green LED lights up continuously on the keypad to indicate the door has been unlocked. The door must then be pushed in order to open it. A magnet in the cockpit is used to keep the door in the open position.

- If the flight crew moves the switch to the LOCK position, the door is kept locked. The acoustic signal stops. The red LED lights up continuously on the keypad to indicate locking is voluntary. Any interaction with the keypad is then disabled for 5 minutes (until the extinction of the red LED). At any time, the crew in the cockpit may cancel this locking by placing the switch in the UNLOCK position. The door then immediately unlocks.

- In the absence of any input on the switch, the door remains locked. No LEDs light up on the keypad. The acoustic signal stops after one second.”

It is significant that after just

one access request at 09:34, no further request is recorded on the door lock.

It is reasonable to assume at this point that the selector switch inside the

cockpit was put in “Locked” position, thereby disabling the keypad for 5

minutes. However, did the Captain not know about this 5 minute interval? Why

did he not make yet another attempt 5 minutes later, at about 09:39 to use his

emergency access code?

As highlighted in my earlier blogposts

also, human error is not a disease. It is a symptom of the disease called “Poor

Organizational Management”. Several flaws in Germanwings and Lufthansa

management have been highlighted by this accident and it is those shortfalls in

management that created the setting in which the accident scenario could be

played out. Lufthansa has much to learn from this accident about management of

human resources and about preventing humans from erring. As for Germanwings, if

they thought safety was expensive, they have now had a taste of an accident.

The writing is already on the wall…investors have already decided to liquidate

the Germanwings brand and merge the assets with Europewings. This is not the

first time an airline has had to be liquidated because of an accident, and

unless the managements learn very quickly about managing humans like humans and

not objects, I fear that this will not be the last time also!

Stay Safe,

The Erring Human.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)