The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) was tasked by the

European Commissioner to establish a Task Force to look into the accident of #GermanWings

flight 9525 including the findings of the French Civil Aviation Safety

Investigation Authority (BEA) preliminary investigation report.

Chaired by EASA Executive Director, the Task Force consisted

of 14 senior representatives from airlines, flight crew associations, medical

advisors and authorities. Additional contributions were provided by invited

experts and representative bodies. Three formal Task Force meetings took place

from May to July 2015.

As a result of its work, the Task Force delivered a set of 6 recommendations to the European Commission on 16 July 2015, as

follows:

- Recommendation 1: The Task Force recommends that the 2-persons-in-the-cockpit recommendation is maintained. Its benefits should be evaluated after one year. Operators should introduce appropriate supplemental measures including training for crew to ensure any associated risks are mitigated.

- Recommendation 2: The Task Force recommends that all airline pilots should undergo psychological evaluation as part of training or before entering service. The airline shall verify that a satisfactory evaluation has been carried out. The psychological part of the initial and recurrent aeromedical assessment and the related training for aero-medical examiners should be strengthened. EASA will prepare guidance material for this purpose.

- Recommendation 3: The Task Force recommends to mandate drugs and alcohol testing as part of a random programme of testing by the operator and at least in the following cases: initial Class 1 medical assessment or when employed by an airline, post-incident/accident, with due cause, and as part of follow-up after a positive test result.

- Recommendation 4: The Task Force recommends the establishment of robust oversight programme over the performance of aero-medical examiners including the practical application of their knowledge. In addition, national authorities should strengthen the psychological and communication aspects of aero-medical examiners training and practice. Networks of aero-medical examiners should be created to foster peer support.

- Recommendation 5: The Task Force recommends that national regulations ensure that an appropriate balance is found between patient confidentiality and the protection of public safety. The Task Force recommends the creation of a European aeromedical data repository as a first step to facilitate the sharing of aeromedical information and tackle the issue of pilot non-declaration. EASA will lead the project to deliver the necessary software tool.

- Recommendation 6: The Task Force recommends the implementation of pilot support and reporting systems, linked to the employer Safety Management System within the framework of a non-punitive work environment and without compromising Just Culture principles. Requirements should be adapted to different organisation sizes and maturity levels, and provide provisions that take into account the range of work arrangements and contract types.

Following the 11 September 2001 attacks, several measures

were introduced to mitigate the risk of unwanted persons entering the cockpit.

Secure cockpit door locking was rapidly mandated, and rules were subsequently

fine-tuned to address the risks in the areas of rapid aircraft

depressurisation, double pilot incapacitation, post-crash cockpit access, and

door system failure including manual lock use.

The focus for all the measures that were introduced was put

on the threat from outside of the cockpit. A potential threat from inside the

cockpit was not fully considered in either the initial phase or the period that

followed, when the regulations were fine-tuned.

As I have also pointed out in my earlier blog posts in this

blog, the risk mitigation measure introduced to mitigate the risk of unlawful

interference (Secured Cockpit Door) has actually facilitated the very event it

was meant to prevent! There have been many cases, even before #GermanWings

9525, where the secure cockpit door was locked from inside by a rouge pilot,

preventing the other pilot from entering, while he proceeded to unlawfully

interfere with the flight by hijacking or crashing it. The risk mitigation

measure had been introduced and implemented in a hurry, without a full

assessment of Residual Risks or Additional Risks created by its implementation.

This was a mandate that the EASA task force was charged

with. Here was an opportunity to carry out a professional risk assessment and

properly evaluate all the additional/residual risks and develop a system to

mitigate them as well. Here was an opportunity to reform the cockpit door

technology and to improve the procedures surrounding its use. Here was an

opportunity to, maybe, introduce new technology; develop new policies and/or

new procedures.

Unfortunately, the task force has missed the bus! They have

chosen to limit themselves to the “2-persons-in-the-cockpit recommendation”,

instead of being more creative and developing further on this base to introduce

more security measures in addition to merely two-persons-in-the-cockpit. The

technology today has advanced considerably since the days of 2001 and many

additional and secure measures are today possible beyond the mere four digit

numeric code to lock or open a door. These additional measures, like biometrics

etc., are not only readily available but are competitively priced and readily implementable.

I was reminded by my colleague, Carlo Cacciabue, of

Professor James Reason’s ground breaking research and work on Safety Management

Systems. He used to say, mistakes by humans, be they errors or violations, are

like mosquitoes. You can try to swap them individually, but they will keep

coming back. The only way to save ourselves from being bitten is to drain the

swamps where these mosquitoes breed. All human performance happens inside an

organizations policies and procedures. Erroneous or insufficient policies/procedures

are the swamps where these mosquitoes called errors and violations breed. Unless

we develop organizations measures to prevent breeding of these mosquitoes, we

will never be able to prevent another event like #GermanWings 9525!

It is very unfortunate that the EASA Task Force has failed

to deliver any meaningful recommendation. One did not need a task force to

arrive at the very basic and on-the-surface kind of recommendations that have

emerged here. We all knew this within days of the accident. What one expected

from a task force of this level was a more professional risk assessment and

recommendations in tune with the complexity of the problem. The task force

needed to go into the depth of this problem and emerge with recommendations

with far reaching impact on safety of civil aviation. It needed to develop

organizational policies and procedures for dealing with distressed employees

and those that need help, in addition to a complete relook and revamp of how we

secure our cockpits.

Once again, it has been forgotten that at the end of the

day, pilots are as human as rest of us and susceptible to as many human

problems and issues as the rest of us. Any human can be regulated only to a

certain extent. There is a limit to the amount of stress and regulation that

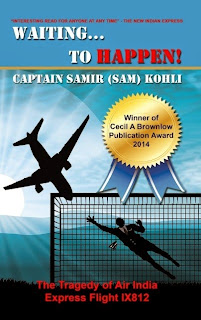

can be piled onto a specific job role. The Pilots are the goal keepers of the

Aviation industry…and a goal keeper can only save so much if rest of the team

does not support the aim of winning the match!

An opportunity has been missed, and yet another accident, similar

to #GermanWings remains waiting…“Waiting…To Happen!”.

Stay Safe,

The Erring Human.